In most cities, the task of replacing lead service lines (LSLs) has stretched over 20 to 25 years. The City of Newark, New Jersey, however, set an unprecedented pace, removing all of its LSLs in just over two years. This accomplishment, which transformed a crisis into a positive story, reflects recommendations made by a Lead in Drinking Water Task Force organized by Jersey Water Works, a nonprofit collaborative that produced the nation’s first statewide, cross-disciplinary study of the problem in October 2019. How did Newark move so quickly?

First, a bit of background. From 2017 through 2019, Newark experienced several consecutive exceedances of the federal limit for lead in drinking water. The situation turned dire in the summer of 2019, when concern over the effectiveness of water filters provided by the city triggered the distribution of bottled water to affected residents. Decisive action was needed.

To jumpstart the program, the city arranged a fairly unique funding source. In September 2019, Newark settled long-standing negotiations with the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey over the lease of city-owned property supporting Port Newark and Newark Liberty International Airport, generating $155 million in new revenue over a 30-year period. This provided a funding source to repay a $120 million bond for LSL replacement issued through the Essex County Improvement Authority. Through this partnership, Newark took advantage of the authority’s triple A bond rating, ensuring the best credit terms.

Most cities rely on increases in water rates to finance LSL replacement, and stretching the work over a long time period helps avoid politically unpopular rate shocks. While Newark skirted that problem, the pace of the city’s program was not solely attributable to its unique financing. Strong leadership, elimination of cost share requirements, leveraging of existing strengths, policy innovation, aggressive contract management/oversight, and public engagement were equally important.

Leadership

Kareem Adeem, director of Newark’s Department of Water and Sewer and a Lead in Drinking Water Task Force member, was instrumental. Having spent three decades with the Department—starting with a pothole crew in 1991—he understood the challenges. Determined to change the narrative, he worked closely with Mayor Ras Baraka:

“The Mayor wanted this done as quickly as possible, not only for the health and peace of mind of the residents, but also to show that Newark could efficiently and expeditiously solve its own problems.”

Mayor Baraka subscribes to former mayor Kenneth Gibson’s motto: “Where America is going, Newark is going to get there first.” The city was not going to wait to be saved.

Avoiding the “Voluntary Pay and Participate” Delay

In many cities, property owners are required to share in the cost of replacing the portion of the service line that lies beneath private property. The time-consuming process of chasing down individual cost shares significantly lengthens the project schedule, prolonging exposure to the pernicious health effects of lead. This approach, in which LSLs are replaced in a staggered fashion as landlords and residents sign on, is also highly inefficient.

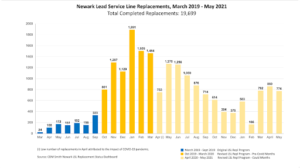

Newark’s initial eight-year program, launched in March 2019, required a cost share of $1,000 from each property owner. The public response was tepid (see LSL replacement chart below), so much so that when the city revised the program in September 2019, the cost share requirement was eliminated. As a result, Newark was able to methodically replace LSLs on a neighborhood-by-neighborhood basis. Compared to individual replacements, this approach produced an estimated cost savings of approximately 13% per LSL, as it shrunk the amount of time required for contractors to move equipment and employees between sites. It was also a prime factor in accelerating the project timeframe.

From the program’s inception in March 2019 through May 2021 the city replaced all of the LSLs that were known to exist. From May 2021 through January 2022 the city gradually addressed approximately 5,000 LSLs whose composition was initially unknown. As depicted in the chart below, the pace increased dramatically after the program was revised in September 2019. Of the 19,699 LSLs replaced through May 2021, only 4% (803) were removed during the first six months of the program (i.e., March 2019 through August 2019), an average of 134 per month. In contrast, during the subsequent 21 months from September 2019 through May 2021, 18,896 LSLs were replaced, representing 96% of the total LSLs that were known to exist up to that point. The monthly average of 900 for that period was nearly seven times faster than prior months despite pandemic-related, operational restrictions.

Leveraging Existing Strengths

Typically, ownership of water service lines is bifurcated, with portions owned by the water utility and the property owner. In Newark, however, all of the lines are privately owned. While many water utilities lack accurate service line inventories (particularly for customer-owned lines), the city possessed good records because the Department had historically prioritized that work. Newark used this data to prioritize neighborhoods most likely to be lead-rich.

Policy Innovation

The elimination of a property owner cost share was not the city’s only innovation. It also pioneered legislation authorizing access to private property and instilled a unique jobs component.

In September 2019, Newark became the first city in New Jersey to enact an ordinance that mandated participation. (Taking Newark’s lead, a similar state law was subsequently enacted in January 2020.) Even if the owner fails to register for the program, the city may access the property to verify and replace a LSL. Approximately 75% of city residents are tenants, who were authorized under the ordinance to provide access. This particular aspect of the program proved particularly helpful in dealing with landlords who were unreachable or recalcitrant.

Newark’s jobs component increased employment opportunities for residents and maximized the impact on the city’s economy. Through an innovative partnership between contractors, local unions, and the city, 35 residents completed an apprenticeship to replace LSLs and receive training in construction trades. Since approximately two-thirds of the apprentices were previously unemployed and many others held minimum wage jobs, the average pay of $25 per hour ($40/hour with overtime) provided a significant boost in income. Newark’s Department of Affirmative Action screened the candidates and provided transportation to training sites. The hiring also helped contractors comply with affirmative action goals. As an ancillary benefit, apprentices’ familiarity with local neighborhoods enabled them to contact property owners who were not home during LSL projects and built community trust by answering questions at public meetings. Many of the apprentices secured permanent positions. Adeem summed it up this way:

“By asking our contractors to train Newark residents for the job, we restored community wealth by providing lifelong skills in the construction trades. The apprentices also gained a sense of satisfaction from working in their own community.”

Contract Management and Oversight

To maximize productivity and hasten completion, Newark applied a number of key oversight principles:

- Hired a project management consultant (CDM Smith) with whom it shared oversight responsibility.

- Contracted with multiple contractors to maximize the number of field crews (30 in peak periods).

- Negotiated aggressive schedules with contractors, including specific performance metrics (e.g., LSLs replaced per field crew per month).

- Installed software/dashboards (e.g., E-Builder, ARC-GIS) that tracked each contractor’s progress in real time, including spatial monitoring (i.e., neighborhood maps) and verification of work quality.

- Twelve consultant staff were assigned to the field to check on work in progress and resolve issues.

- Batch processed required permits (e.g., plumbing, roadway) across entire neighborhoods, eliminating the need for LSL contractors to do so, and waived the usual fees.

- Tracked post-replacement water testing, including mailing of test kits and follow-up on exceedances.

Public Engagement

Realizing the importance of effective outreach to residents, Newark developed a three-pronged approach.

- A comprehensive website highlights the number of LSL replaced and enables residents to determine if their property is served by a LSL, verify eligibility for a water filter, and submit necessary forms (e.g., right of entry) online.

- To help convince residents of the dangers of lead exposure, the city engaged several “trusted voices” among community and faith-based organizations, such as Clean Water Action, Ironbound Community Corporation, and Newark People’s Assembly, which employed a variety of techniques, including door-to-door canvassing.

- 120Water, a technology and communications company that specializes in digital solutions to water-related problems, helped develop a customer-friendly sampling program, “The Newark Way of Thinking and Drinking,” to verify drinking water quality after LSL replacement, increasing the rate of return of water testing kits to the city.

Today, Newark is one of a select few cities in the country that has completely eradicated its lead service lines. Its record pace accelerated a vital health benefit to city residents and established a model that others may wish to emulate.

1 https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5ad5e03312b13f2c50381204/t/5daf07f6e298021e8365cf82/1571751926771/LSLR+Ordinance+20190910.pdf